The demand for a caste Census has become a heated political issue, fuelled by calls from opposition leaders, NGOs, and, more recently, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) also adding itself to the cohort. Proponents argue that such a Census would determine the population sizes of various castes and that these numbers can be used to provide a proportionate share to each caste in government jobs, land, and wealth.

This article discusses how the attempt to collect individual caste data will once again prove to be a futile exercise, and how individual caste-based proportionate reservations is a regressive policy.

Caste Census: a historical background

The exercise of a caste Census in India dates back to the late 19th century when the first detailed caste Census was conducted in 1871-72. It attempted to collect caste-based information and classify various groups, and was conducted across four major regions — the North-Western Provinces (NWP), the Central Provinces (CP), Bengal, and Madras.

There were several arbitrarily constituted “sets” based on a very superficial understanding of caste. In the NWP, for instance, only four sets were officially recorded — Brahmins, Rajputs, Banias, and “other castes of Hindus”. Meanwhile, in the CP, groups such as “servants and labourers” and “mendicants and devotees” were arbitrarily included under these sets. Some of Bengal’s classifications included beggars, musicians, and cooks, while Madras added “mixed castes” and “outcastes” as distinct categories.

Frustrated with the complexities of understanding caste, W. Chichele Plowden, who prepared the 1881 Census report, termed the whole question of caste ‘confusing’ and hoped that ‘on another occasion no attempt will be made to attempt to obtain information as to the castes and tribes of the population’. However, the same issues persisted in the caste Census of 1931 where 4,147 castes were identified. The officials were surprised to find that caste groups frequently claimed different identities in different regions.

These challenges are not relics of the past but continue to shape the difficulties India faces to conduct a caste Census today. For instance, the Socio-Economic and Caste Census (SECC) of 2011 identified over 46.7 lakh castes/sub-castes with 8.2 crore acknowledged errors. A more recent example is the controversy surrounding the inclusion of ‘hijra’ and ‘kinnar’ as categories in the caste list in the Bihar Census (2022).

Challenges to access accurate data

Upward caste mobility claim —the reporting of one’s caste by respondents can be influenced by the perceived prestige associated with certain social groups and their position within the varna hierarchy. This is evident from changes in caste claims between the 1921 and 1931 Censuses, where some communities that initially reported belonging to lower positions within the varna system in 1921 later reported themselves as belonging to higher categories in 1931 (see Table 1). Another notable observation from these claims is that different members of the same community, such as Sonar, reported belonging to different social categories —Kshatriya and Rajput in 1921, and Brahmin and Vaishya in 1931, in the same region (see Table 1). These occurrences were noted in colonial Censuses but their implications remain relevant even today.

Downward caste mobility claim — some respondents may claim to belong to a group positioned lower in the social hierarchy, particularly when they are aware of the potential benefits associated with such affiliations. Notably, these downward social group mobility claims are predominantly a post-independence phenomenon likely due to the advantages associated with reservation policies ( such as when some upper castes demand OBC status/ some OBCs demand ST status).

Problem of caste misclassification — similar-sounding castes and surnames often lead to confusion in caste classification. For example, in Rajasthan, surnames like ‘Dhanak’, ‘Dhankia’, and ‘Dhanuk’ are classified as SC, while ‘Dhanka’ is listed as ST. Similarly, the surname ‘Sen’ refers to an upper-caste group in Bengal, whereas ‘Sain’ is associated with the OBC barber community. Enumerators may mis-record such surnames, inadvertently placing communities in incorrect social categories. Additionally, caste remains a sensitive issue, which may make both respondents and enumerators uncomfortable discussing it directly.

As a result, enumerators might avoid asking about caste explicitly and instead make assumptions based on surnames, further increasing the risk of misclassification.

On proportional representation

Proportional representation in reservations may appear fair at first glance, but upon closer inspection, it becomes clear that it is both impractical and regressive. The system of reserving positions based on a reserved category’s quota is straightforward: the reserved posts are determined by dividing 100 by the percentage of reservation allotted to that reserved category. For instance, since the reservation for OBCs is 27%, every 4th position in a sequence of vacancies would go to an OBC candidate (100/27 = 3.7, rounded up to 4). Similarly, an SC candidate would get every 7th position (100/15 = 6.7, rounded to 7), an ST candidate every 14th position (100/7.5 = 13.3, rounded to 14), and an EWS candidate every 10th (100/10 = 10).

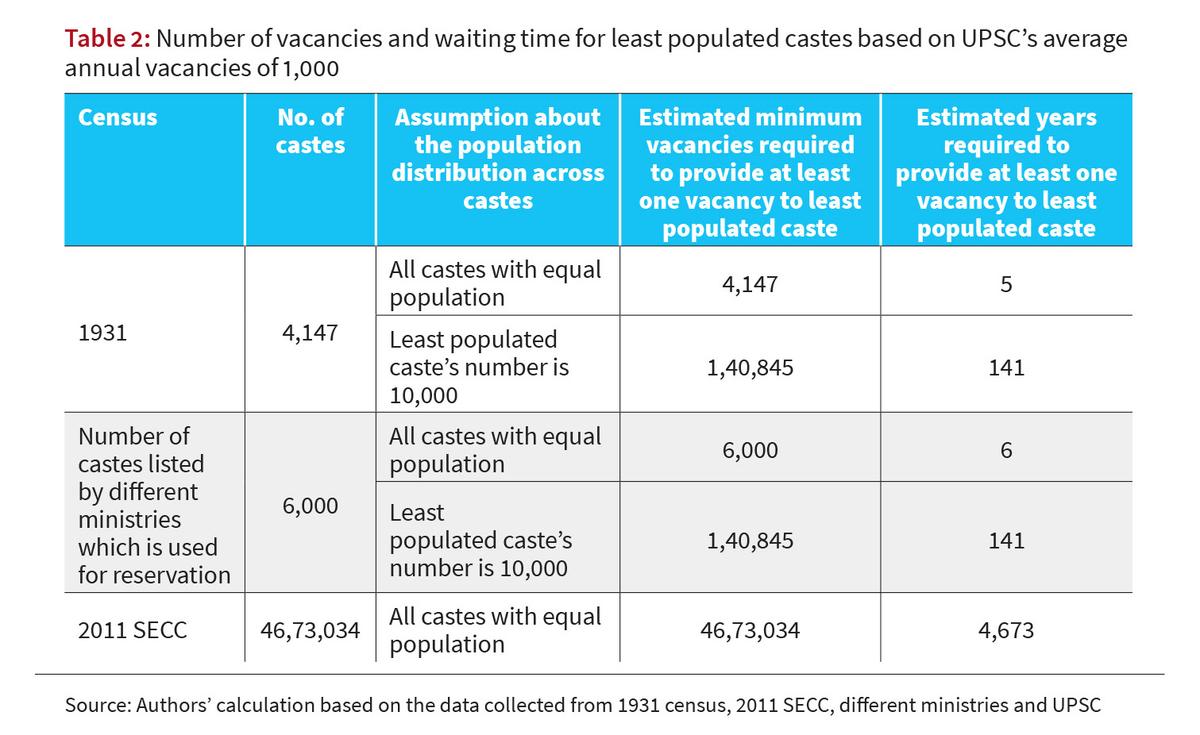

However, significant flaws emerge when proportional representation formulas are applied to individual castes. According to different ministries data, there are around 6,000 castes. Assuming India’s population is approximately 1.4 billion, the average population per caste would be around 2.3 lakh.

To illustrate the challenges of implementing proportional representation at the individual caste level (see Table 2), consider a hypothetical caste ranked last with a population of just 10,000 (0.0007% of the total population). For this caste to secure just one reserved vacancy in an institution, at least 1,40,845 positions would need to be advertised. Using the UPSC as an example, which typically advertises around 1,000 vacancies annually, it would take 141 years for the least populous caste to receive a single vacancy. To make matters worse, if we consider 46.7 lakh castes/subcastes as reported in SECC 2011, the number of vacancies required will be 46,73,034 and the UPSC will take more than 7,000 years to provide the first vacancy to the least populated caste.

Hence, the idea of proportional representation at the level of individual castes proves to be regressive, as it disproportionately excludes the least populous castes from accessing the benefits of reservation.

Anish Gupta teaches economics at the Delhi School of Economics. Shubham Sharma is a Research Associate at the Institute for Educational and Developmental Studies (IEDS), Noida

Published – December 05, 2024 08:30 am IST