The story so far: With a delayed start for the southwest monsoon, which wreaked havoc in parts of the country when it finally arrived, discussions are rife on whether India will continue to see erratic monsoons in future as well. Catastrophic flooding events due to extremely intense spells of rainfall have become a norm in India during monsoon over the last few years.

Although there are a multitude of factors causing them, there is general consensus among scientists that climate change is playing a major role in causing these extreme weather events. This is particularly concerning to India due to the importance of the unique weather system that brings the much needed rain to the subcontinent.

What is monsoon?

Although monsoon is generally associated with rains, it is much more than that. It is the seasonal, inter-hemispherical change in direction of the prevailing winds causing wet and dry seasons throughout the tropics. For instance, the Southwest monsoon that brings rain to the subcontinent during June and July happens due to the heating up of the Asian landmass in the northern hemisphere during the scorching summer and the relatively cooling of the southern Indian ocean. “This results in a low pressure situation over much of Asia and high pressure near Madagascar in the southwestern Indian ocean. Naturally wind blows from high to low pressure region, and due to the curvature and the rotation of the Earth, the circulation turns toward India, bringing rainclouds with it,” explains Dr. Abhilash S., Director of Advanced Centre for Atmospheric Radar Research, Kochi.

Why is monsoon so important to India?

Women farmers work at a field amid monsoon rains, on the outskirts of Hyderabad

| Photo Credit:

PTI

The monsoon is the lifeblood of the country’s $3 trillion economy, delivering nearly 70% of the rain that India needs to water farms and recharge reservoirs and aquifers. The fortunes of the agricultural sector of India heavily relies on the seasonal and properly distributed rains, as planting and harvesting are all planned around them.

Therefore, any drastic change in monsoon rains will severely affect the Indian economy and the livelihoods of millions. This was evident last year when erratic monsoon severely affected the Kharif harvest with the country having to rely on its stock to avert crisis.

How is climate change affecting it?

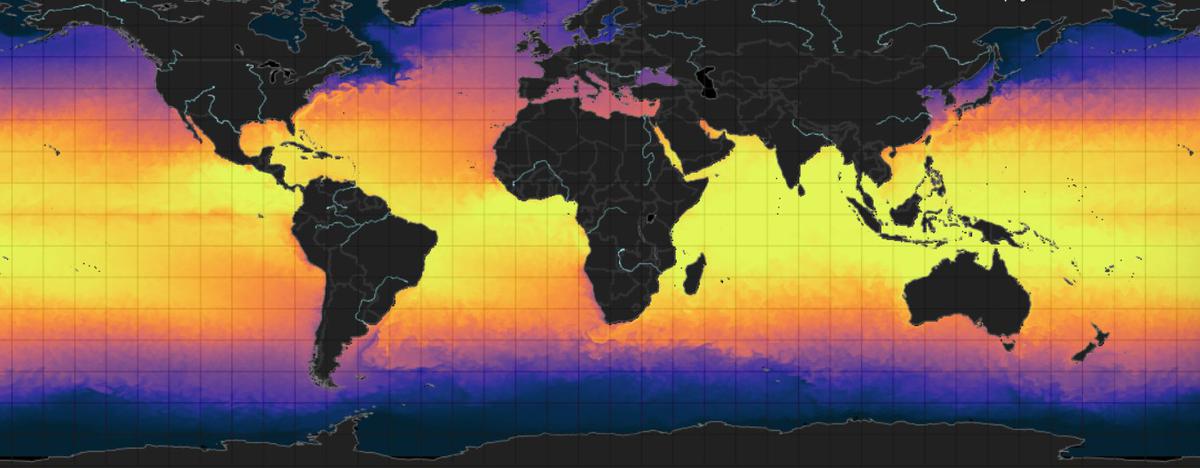

Global ocean and sea water temperature map

| Photo Credit:

UNEP

Since Indian monsoon is an inter-hemispherical phenomenon, any significant change in circulation and weather patterns around the world can affect it as well. This year there was the added influence of Cyclone Biparjoy that formed in the Arabian Sea and delayed the start of the monsoon.- Moreover, scientists are also observing how the declared El Nino will affect the monsoon.

However, experts believe climate change is a main culprit in how monsoon is changing, and that the visible imprints of this change have been observed by climatologists for a while now. “The onset of monsoon itself is showing a lot a changes, mainly due to the warming of Arabian Sea and Indian Ocean. Indian Ocean has been warming at a much higher degree (1.1 degree Celsius over the last 100 years) than other Oceans, and much of this warming has happened in the last 50 years. This disparity is due to the landlocked nature of the Indian Ocean, which can only dissipate the excess heat through its southern side, while Pacific and Atlantic Oceans can dissipate heat to Polar regions through south and north,” explains Dr. Abhilash. This excess heating of Indian Ocean and Arabian Sea is disturbing the North-South thermal gradient that is causing the monsoon (as explained above), leading to delayed onset due to conditions not being ideal for monsoon winds to occur, as well as erratic rainfall marked by prolonged dry spells, and short extremely intense rains mainly due to the formation of clouds with much more moisture content than usual as a result of deep convection. The atmospheric heating due to global warming is also contributing to this disturbance now.

What are the difficulties that forecasters are facing in predicting monsoon rainfall?

A man points at dark clouds covering Kochi’s skyline, Friday, May 26, 2023

| Photo Credit:

PTI

Weather forecast agencies, like Indian Meteorological Department (IMD), use large mathematical models called dynamical models for making weather predictions. These models, run on supercomputers, are fed with atmospheric and oceanographic data for generating various forecasts, including those related to monsoon rainfall. Former secretary of Ministry of Earth Sciences, Dr. M. Rajeevan says the change in behaviour of monsoon is affecting the forecasting as well.

“The mathematical models we use have some trouble predicting the short-spell heavy rainfalls that we are seeing during monsoon nowadays. The model does have a kind of a bias. For some rains that are 12 cm, the model doesn’t really pick up 12 cm and might only show 7 or 8 cm. However, it gives indications that it would be above that value. So, there is a systematic bias in the model that makes it underestimate the amount of heavy rainfall. With global warming and climate change, the frequency of these heavy rainfalls is going to increase. Therefore, these kind of errors can get accumulated in future forecasts,” he explains.

To improve the short-range rainfall forecast that predicts rains for the next four to five days, models will have to be improved. This will require a better understanding of cloud physics, especially micro-physical processes happening inside the cloud. “We don’t really use many of the physical processes accurately in the model. For instance, about how cloud forms, how it rises up and how it produces rainfall, that is the cloud micro-physical processes. We don’t much. What all we know, we have used in the model. But there are many unknown things about cloud physical processes, and land-surface processes. Therefore, we need more data and more fundamental research,” adds Dr. Rajeevan. There is also a need to improve the resolution of forecasts and assimilate more date regarding wind movements, especially vertical profile of winds above the ocean, which will require better satellite readings.

However, he says that modelers are currently working on correcting this bias and improving the models.

How is a changing monsoon challenging disaster management?

These changes to monsoon rainfall pattern are causing severe challenges to disaster management as well.

A view of the landslides following the heavy rain at Thodiel near Paravoor in Kannur in August 2022

| Photo Credit:

MOHAN SK

Speaking of the disasters that Kerala has been facing over the past few years, chief scientist of the State Disaster Management Authority, Dr. Shekhar L. Kuriakose admits that a good portion of the blame for these disasters do fall on the land-use pattern. However, the changes in rainfall pattern too is a major factor, especially the number of rainy days getting crunched is a big issue. “The difficulty of that is, a large amount of rainfall gets concentrated in a place, causing flash-floods, debris flows and landslides, as against a more evenly distributed rainfall pattern contributing to sub-surface water storage and reservoir water storage,” he says.

What is Orange Book?

Containing information on emergency response assets available across Kerala, the ‘Orange book of disaster management — Kerala — SOP and emergency support functions plan’ explains the standard operating procedure for rainfall, flood, cyclone, tsunami, high waves (swell waves, storm surges, ‘kallakadal’), landslips, petrochemical accidents and even mishaps caused by space debris (meteorites, falling spacecraft parts, etc.).

Meanwhile, the ‘Monsoon preparedness and emergency response plan’ is season-specific, and meant to be strictly complied with during the south-west and north-east monsoon seasons (June to December).

Dr. Shekhar believes that systems seem to be rapidly changing, and is not showing any predictable patterns for disaster managers to rely on a static, centralised management plans to tackle rain-related disasters will not be enough. “In the past when Disaster Management Act (2005) was passed, the discussions were all about mitigation plans. They more or less static documents with an annual review. Now, Kerala had to deviate from that. The dynamic parts of that annual plan had to be brought into a very unique document called the orange book, which is country’s only one, and which actually gets updated every year and directs every department to facilitate emergency response services. There are also anticipatory actions planned in there. That became essential”, explains Dr. Shekhar.

There has also been considerable decentralisation in disaster response as local bodies have been trained and empowered for disaster management. This shift largely occurred post 2018 floods in Kerala. Dr. Shekhar adds, “We started with a massive program called ‘Nammal Namukkayi’ to localise disaster management. Aligned to that we also created civil defence across the State, making Kerala India’s only state to have civil defence notified pan state.” This change is reflected in fund dispersal too with local bodies now being able to access funds to prepare for disasters rather waiting for government funds after an event has occurred. Moreover, those living in disaster prone hilly and coastal areas are being encouraged to shift to safer grounds by providing them with land, housing or financial incentives to relocate.