Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhatever the new government chooses to focus on in the King’s Speech, it faces big and immediate challenges it will not be able to ignore.

Here are some of the most pressing issues Labour has said are part of its inheritance.

Public sector pay

Decisions on pay rises for NHS staff, teachers, police and prison guards in England have to be taken by the end of this month, when the official public sector pay review process for 2024-25 must be concluded.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) estimates that the government would need to find at least an extra £7bn per year to prevent the wages of these public sector workers falling further behind their counterparts in the private sector.

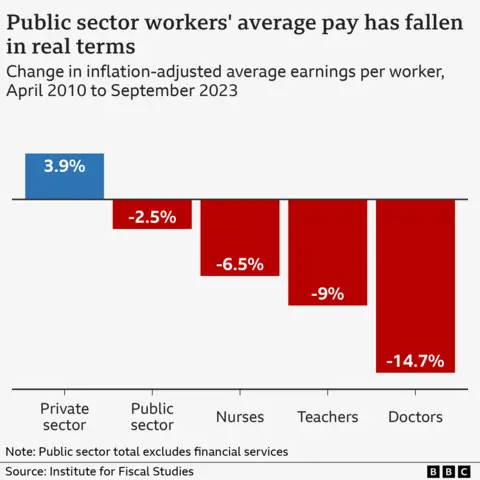

Data from the IFS shows that while average private sector inflation-adjusted wages are around 4% higher than in 2010, public sector wages are still around 2.5% lower.

The average pay for nurses is down 6.5% over that time, teachers’ wages are 9% lower and doctors’ 15% lower.

Finding £7bn per year extra would be very challenging given the government’s chosen fiscal rules, which restrain its spending and taxation powers.

But if it fails to do this, it could find its targets to recruit more teachers and nurses even harder to achieve – or even risk provoking further public sector strikes.

Local councils

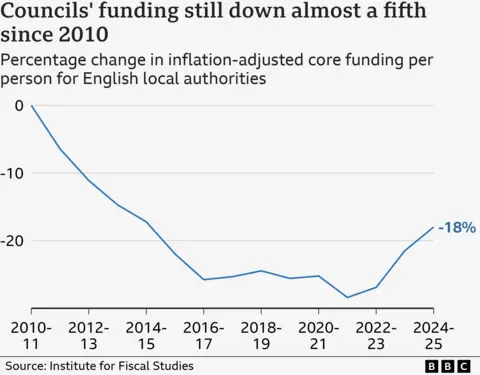

Local authorities in England are in a financial crisis. Five have gone into effective bankruptcy since the start of 2023, forcing deep cuts to local services.

And this situation is set to worsen.

A survey of local authority leaders by the Local Government Information Unit earlier this year found around 28 local authorities – about one in 10 – were likely to have to effectively declare bankruptcy this financial year (2024-25).

And around half, or 160, said they were likely to go bust during this Parliament unless local government funding is reformed.

Ministers could give struggling councils a direct financial top-up to keep them afloat. But that would be expensive for the Treasury.

They could allow local authorities to increase council tax even further. They might also allow them to reduce the local services they are required by law to offer, such as social care, children’s services and libraries.

But neither of those two options is likely to be popular among local residents.

Universities

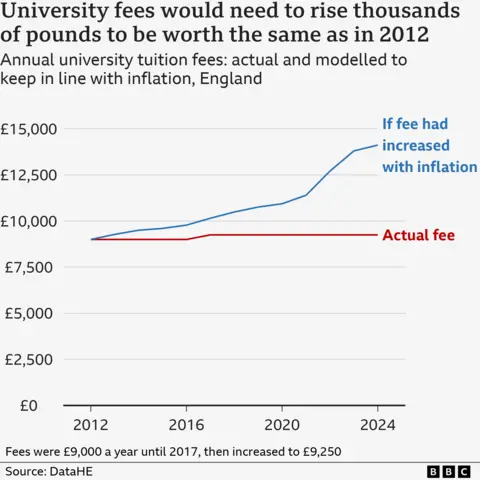

The £9,250 per year tuition fee that universities in England can charge domestic students has been frozen in cash terms since 2017, contributing to a reduction in the inflation-adjusted income per student for universities of around 18% over the past decade, according to the IFS.

Had fees increased using the RPIX measure of inflation, they would now be more than £14,000 a year.

This, combined with a recent fall in income from foreign students, has led to warnings from the Higher Education Policy Institute that there is a “real risk” a university could go bankrupt in 2024.

Do ministers allow universities to generate more income by raising the tuition fee? That would not go down well with students.

Or do they signal that the government will allow universities to recruit more lucrative overseas students who pay uncapped tuition fees – and risk criticism from those who want to see a large reduction in net migration?

Prisons

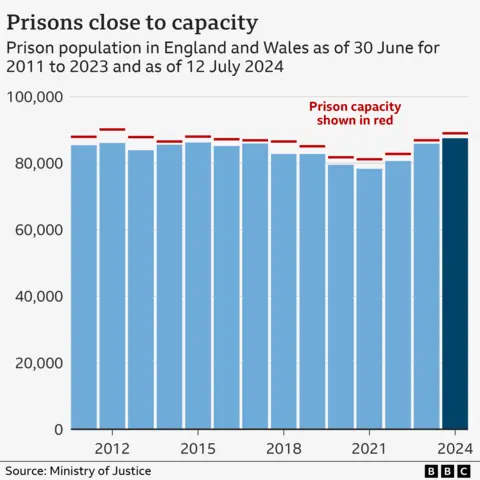

Prisons in England and Wales had just 1,451 places available at the end of last week, meaning they are 98% full, according to Ministry of Justice data.

The government has decided that from September there will be temporary early release for some prisoners when they have served just 40% of their sentence to relieve the pressure.

But experts warn that will only create short-term breathing space for the system.

The bigger policy choice for the government is whether to step up the prison building programme to cope with the demand for places – at a considerable cost for the Treasury – or seek to reduce the prison population through permanent sentencing reform, which some would likely characterise as “soft on crime”.

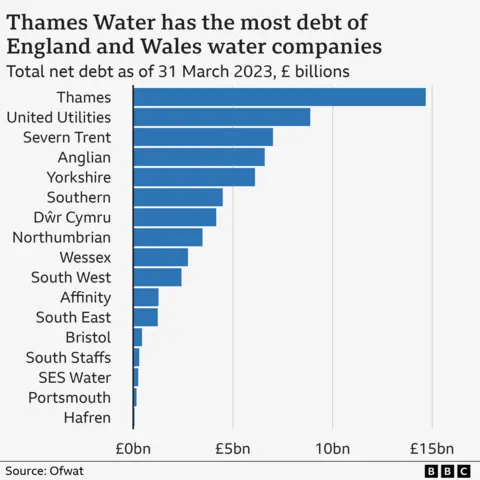

Thames Water

Thames Water’s latest report for the year to March 2024 revealed it has debts of £15.2bn, which it is struggling to repay. It only has sufficient cash to last until May 2025.

If Thames fails it will likely go into a government “special administration” regime – a form of temporary nationalisation – in order to ensure some 16 million households in the South East of England keep getting their water.

Does the government wait and hope the situation improves and the company can raise the private sector money it needs to keep going? Or should it grasp the special administration nettle earlier?

The risk of waiting is the ultimate cost of the rescue process to the taxpayer could end up being higher. And the crisis could potentially spread to other private water companies with weak finances.

Additional reporting by Daniel Wainwright, Pilar Tomas and Phil Leake.