Getty Images

Getty ImagesThames Water’s attempt to secure its future continues to hang in the balance as the government takes the precautionary step of lining up administrators.

The government has confirmed that FTI Consulting is advising it on a Special Administration Regime (SAR), should the UK’s biggest water company collapses.

In July, Thames warned it was “extremely stressed” and posted huge annual losses.

The company has huge debts and is struggling to fix leaks, stop sewage spills and modernise outdated infrastructure.

It serves about a quarter of the UK’s population, mostly across London and parts of southern England, and employs 8,000 people.

Could Thames fall under government control?

The government said on 12 August that Thames Water remained “financially stable”, but it had “stepped up” preparations in case the firm falls into administration.

FTI Consulting is advising the government on SAR contingency planning – this would happen if Thames becomes insolvent, cannot fulfil its duties or breaches an enforcement order.

If the firm does go bust, households will still have drinking water and sewerage services.

Thames said it was focused on making itself financially viable and that “constructive discussions with our many stakeholders continue”.

The GMB union said the firm had been “sacrificed on the altar of privatisation”.

The likelihood of Thames collapsing into a SAR increased after US private equity giant KKR pulled out of plans to buy the company in June, although the company continues to court investors.

What happened with KKR?

KKR had been selected as the preferred partner to inject £4bn of much-needed cash into Thames.

It is one of the world’s largest private equity firms with $160bn (£119bn) of investments globally. The firm is already a shareholder in another UK provider, Northumbrian Water.

KKR’s withdrawal came on the same morning that an independent commission released interim findings of a review into how the water industry can be reformed – a review which many saw as potentially supportive in attracting new investment.

Sources close to the situation told the BBC that the politicisation of the water industry was a major disincentive for investors to put money into the sector.

Thames called the news “disappointing” but said it would proceed to work with other potential investors who submitted earlier expressions of interest.

How did Thames end up looking for a rescuer?

Many UK water companies have large debts, but Thames Water’s problems are the worst.

When Thames was privatised in 1989, it had no debt. But over the years it borrowed heavily and its total debt – which includes all of its borrowings and liabilities – now stands at £22.8bn, according to latest financial results.

Its debt pile increased sharply when Macquarie, an Australian infrastructure bank, owned Thames Water, with debts reaching more than £10bn by the time the company was sold in 2017.

Macquarie said it invested billions of pounds in upgrading Thames’s water and sewage infrastructure while it owned the company, but critics argue that it took billions of pounds out of the company in loans and dividends.

What does all this mean for customers?

No matter who eventually owns or runs Thames Water, customers will see no impact on their services. Taps will still run and toilets will still flush.

However, Thames has said it needs to increase its bills to fix problems, with the average annual bill rising by almost a third to £639 in April.

Consumer groups argue people shouldn’t have to pay more because the company has been badly run.

But Sir Adrian Montague, Thames Water’s chairman, warned that without bigger price rises, the company cannot guarantee safe and resilient water supplies that can cope with climate change and population growth.

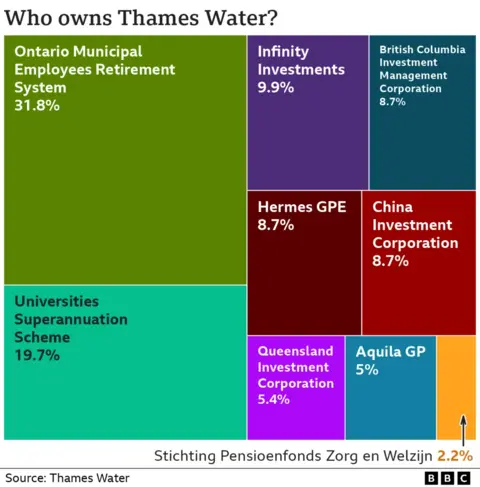

Who owns Thames Water now?

Thames Water is privately owned by a group of pension funds and investment firms. The biggest shareholders include:

- Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System (Canada) – 32%

- Universities Superannuation Scheme (UK) – 20%

- Abu Dhabi Investment Authority – 10%

- China Investment Corporation – 9%

Other investors include funds from Canada, Australia, and the Netherlands.

Why was Thames Water privatised?

The entire water and waste sector was privatised under Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government. At the time, Thatcher wrote off the industry’s £5bn debt, leaving companies with a clean slate, and gave them £1.5bn in public money.

At the time, the UK was under pressure to meet European water quality standard standards. Thatcher wanted the billions of pounds of investment need to do this to come from the private sector and, by extension, companies’ customers.

“If we want environmental improvement, it will cost money,” said Mrs Thatcher in 1988. “It will be the people who want those improvements in water who will have to pay.”

However, critics say that privatisation has not worked as water firms have taken on too much debt while failing to invest in infrastructure.