Introduction

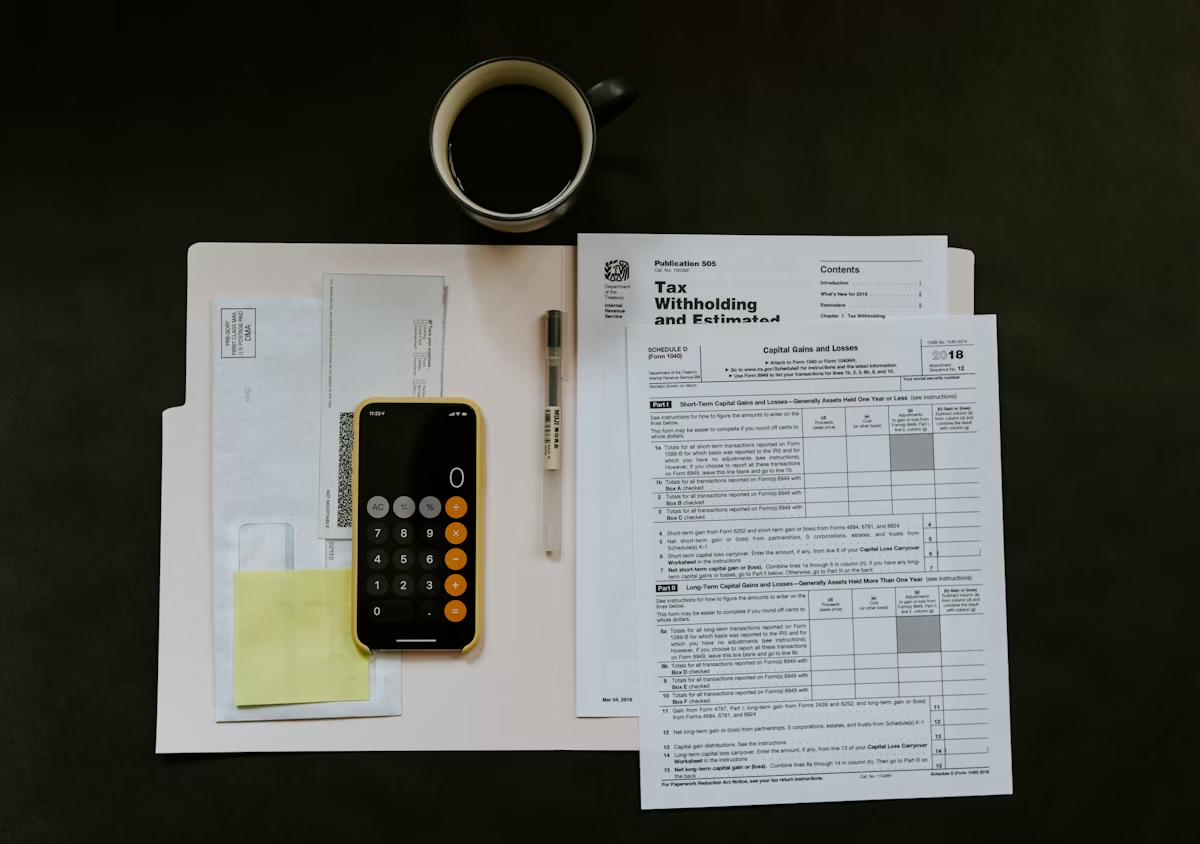

Most borrowers focus on a single number when taking a loan: the monthly payment.

While this number feels important, it hides the deeper reality of borrowing:

The true cost of debt is determined by how interest is calculated over time.

Across mortgages, personal loans, student debt, and credit cards, the structure of interest—simple, compound, fixed, or variable—quietly determines how much money leaves a borrower’s pocket over years or decades.

Understanding this hidden math transforms borrowing from a financial trap into a controlled financial decision.

Why Interest Exists in Lending Systems

Interest is the price paid for:

- Access to capital today

- Risk taken by the lender

- Loss of alternative investment opportunities

In global finance, interest serves as the core engine of credit markets.

But for borrowers, misunderstanding it often leads to long-term financial strain.

Simple Interest vs Compound Interest

Simple Interest

Calculated only on the original principal.

Formula (conceptually):

Principal × Rate × Time

Because interest does not grow on itself,

total repayment remains relatively predictable.

Compound Interest

Compound interest calculates on:

Principal + accumulated interest

This means:

- Debt can grow faster

- Longer repayment dramatically increases cost

- Small rate differences become significant over time

Compound structures dominate:

- Credit cards

- Many long-term loans

- Revolving credit systems

This is why disciplined financial behavior—discussed earlier in market psychology and emotional control also applies strongly to borrowing decisions.

The Hidden Power of Time in Debt

Borrowers often compare:

- Interest rate

- Monthly payment

But ignore the loan duration, which can matter even more.

A slightly lower rate with a much longer term can lead to:

- Higher total repayment

- More interest paid overall

- Slower wealth building

Time quietly multiplies the cost of borrowing.

How Credit Card Interest Becomes Expensive

Credit cards represent one of the most misunderstood debt systems globally.

Key characteristics:

- High annual percentage rates

- Frequent compounding

- Minimum payment structures

Minimum payments are designed to:

Extend repayment duration and maximize total interest collected.

Without aggressive repayment, small balances can persist for many years.

Real-World Borrowing Mistakes

Focusing Only on EMI

Low monthly payments often hide:

- Long repayment periods

- High cumulative interest

Ignoring Early Repayment Opportunities

Extra principal payments made early in a loan:

- Reduce total interest dramatically

- Shorten repayment timeline

Late extra payments help far less.

Using Debt for Depreciating Consumption

Borrowing for:

- Luxury goods

- Lifestyle upgrades

- Non-essential spending

creates no long-term financial return,

only prolonged repayment pressure.

Smarter Borrowing Framework

1. Compare Total Repayment, Not Just Rate

Always evaluate:

Total paid over loan life

instead of only monthly affordability.

2. Prefer Shorter Loan Terms When Possible

Shorter duration means:

- Less compounding

- Lower lifetime cost

- Faster financial freedom

3. Make Early Extra Principal Payments

Even small additional payments early in the schedule:

- Cut years off repayment

- Save significant interest

4. Align Debt With Long-Term Value

Responsible borrowing usually supports:

- Education

- Housing stability

- Business or productivity growth

Not short-term consumption.

Psychological Traps in Debt Decisions

Borrowing is not purely mathematical.

It is deeply behavioral.

Common mental traps include:

- Present bias (valuing today over future cost)

- Payment illusion (low EMI feels affordable)

- Social comparison spending

These patterns connect strongly with the money psychology habits explained in daily financial behavior and wealth formation. Understanding both math and psychology is essential for safe borrowing.

Global Guidance on Responsible Borrowing

Financial education institutions worldwide emphasize:

- Understanding loan terms fully

- Comparing multiple lenders

- Avoiding high-cost revolving debt

Resources such as the U.S. Federal Trade Commission consumer credit guidance highlight transparency and informed borrowing as core protection principles.

Debt as a Tool, Not an Enemy

Debt is not inherently harmful.

In structured contexts, it can:

- Enable asset ownership

- Support education

- Accelerate opportunity

The difference between useful debt and harmful debt

lies in interest structure, duration, and purpose.

Long-Term Impact on Wealth Building

High interest obligations reduce:

- Savings capacity

- Investment potential

- Financial flexibility

Over decades, unmanaged debt can delay:

- Home ownership

- Retirement readiness

- Financial independence

Conversely, controlled borrowing combined with disciplined repayment

supports stable long-term wealth growth.

Conclusion

Interest is not just a percentage on paper.

It is a powerful financial force that shapes long-term outcomes.

Borrowers who understand:

- Compounding

- Time effects

- Behavioral risks

gain the ability to transform debt from a burden

into a carefully managed financial tool.

In the end, smart borrowing is not about avoiding credit entirely—

it is about understanding the math well enough to stay in control.